According to the U.S. Census American Community Survey five-year data (2018-2022), roughly 162 million people over the age of 16 are employed full-time in the United States.

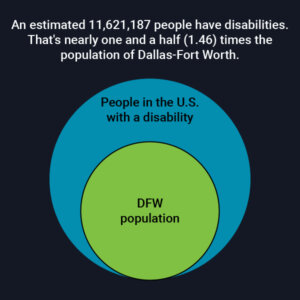

Of that number, an estimated 11,621,187 have disabilities. That’s nearly one and a half (1.46) times the population of Dallas-Fort Worth.

As discussed in our first article, ‘disability’ is an umbrella term that can describe physical and non-physical challenges. The government uses it to assess and distribute social benefits, and it is a way to group people who use accessibility devices or services. However, not everyone likes this term, as they feel it implicitly communicates limitations about their abilities.

This concern can be heightened in the workplace—where Dr. Jason Cohen focused his research when earning his Doctor of Business Administration degree at Franklin University. Combined with his MBA from the University of Connecticut, he is uniquely positioned to talk about neurodiversity in the workplace. Specifically, he studied professionals who are classified as ‘level one autistic’— a diagnosis that he says is increasing.

“That doesn’t necessarily mean that autism itself is more prevalent; more cases could be the result of better diagnostics. But more people being on the spectrum justifies further research and exploration into how to be inclusive,” said Cohen.

Autism is just one example of neurodiversity. But whether a person has visible or non-apparent disabilities, creating an environment where everyone can be their best starts with open communication. That might be a big initial hurdle—either because communication skills are impacted by a person’s diagnosis or because of fear that they’ll be put into a category based on stigma and assumptions of capability.

“The feedback that I got from [the professionals studied] was that when they did disclose, in some cases it was a detriment at first because immediately they had to overcome these stigmas,” said Cohen.

People may understand disabilities through one example. “I’ve watched the ‘Good Doctor,’ so I understand what autism is.” Or — “I know one employee who has a brain injury, so I know how to create a supportive environment for anyone who is neurodiverse.”

Cohen uses himself as an example of how an uninformed approach to disability inclusion can become a performance issue for employees.

“Sometimes I have a problem modulating the pitch of my voice and some people may be like, oh, you don’t really seem excited.”

Though this may seem like a small, easily rectified problem, Cohen must think about modulating his voice to do it. In a competitive work environment, where presentation skills are one factor used to describe someone’s leadership presence and readiness for promotion, he could be penalized.

“There have been studies that show about 10% of your presentation is the content and 90% is how you present it,” said Cohen.

If a manager doesn’t think someone looks like a leader, that person may be consistently passed over for opportunities. Empathy and open communication are the antidotes to these situations, but if individuals don’t feel safe, it’s a conversation that won’t happen.

“There are challenges in doing it right, but consider what companies are losing by not investing in their employees—economically, it’s massive, it’s in the billions in productivity losses, and those numbers just keep compounding,” said Cohen.

A customized approach to disability inclusion

A customized approach to disability inclusion

Michael Thomas founded ConnectIDD (pronounced: connected), an agency that contracts with companies, nonprofits, and municipalities to make them more accessible for people with intellectual and developmental disabilities (IDD). He cautions decision makers not to forget to show their humanity. Adhering to legal guidelines is essential, and demonstrating an understanding of the complexities of disability inclusion will help individuals feel safe to be transparent about the way they experience the world.

“Many times, you can see people tense up when interacting with someone who has a disability. Whether the person has IDD or another difference, that type of reaction suppresses honest conversations,” said Thomas. “You can’t approach disability inclusion the same way in every situation. Beyond just saying they care, organizations need to figure out how to both satisfy legal requirements and be authentically compassionate.”

So, what is the right way to respond if an employee discloses a disability or are experiencing challenges such as focusing, paying attention, or comprehending?

“The first thing the manager should keep in mind is to listen and not speak,” says Sherry Travers, a lawyer specializing in labor and employment law at Littler Mendelson, PC. “Not all words carry the same weight and you don’t want to accidentally say something that will put the company at risk or make the employee feel victimized.”

Travers advises leaning on HR to guide the conversation, making the employee aware of support services that exist inside the company, and following the process for providing reasonable accommodations.

The reasonable accommodation process

Employers may need to provide reasonable accommodation to applicants and employees with disabilities to integrate these individuals into the workforce. For example, a vision-impaired job applicant may have difficulty accessing or using a prospective employer’s website to apply for a job because of an inaccessible user interface. An employee with a cognitive impairment may have trouble meeting their employer’s production requirements.

To determine if an employer can accommodate such applicants and employees in these situations and the type of accommodation needed, the applicant or employee will engage with the employer in what is known as the interactive process. This process is conducted on an individualized basis, considering the evolving nature of the essential job functions and the individual’s functional limitations. The interactive process entails an individual and their employer:

- exchanging information about the individual’s disability and work-related restrictions;

- identifying potential appropriate workplace accommodations; and

- reaching a mutually satisfactory decision about the reasonable accommodation to be provided.

While employers are expected to take the lead role in this process, individuals who request workplace accommodations are equally responsible for engaging with their employers in the accommodation process in a timely and responsible manner.

Development of this story was supported by Michaela Noble, Esq., management-side employment attorney at Littler Mendelson P.C., and Mark Flores, Esq., shareholder at Littler Mendelson P.C.